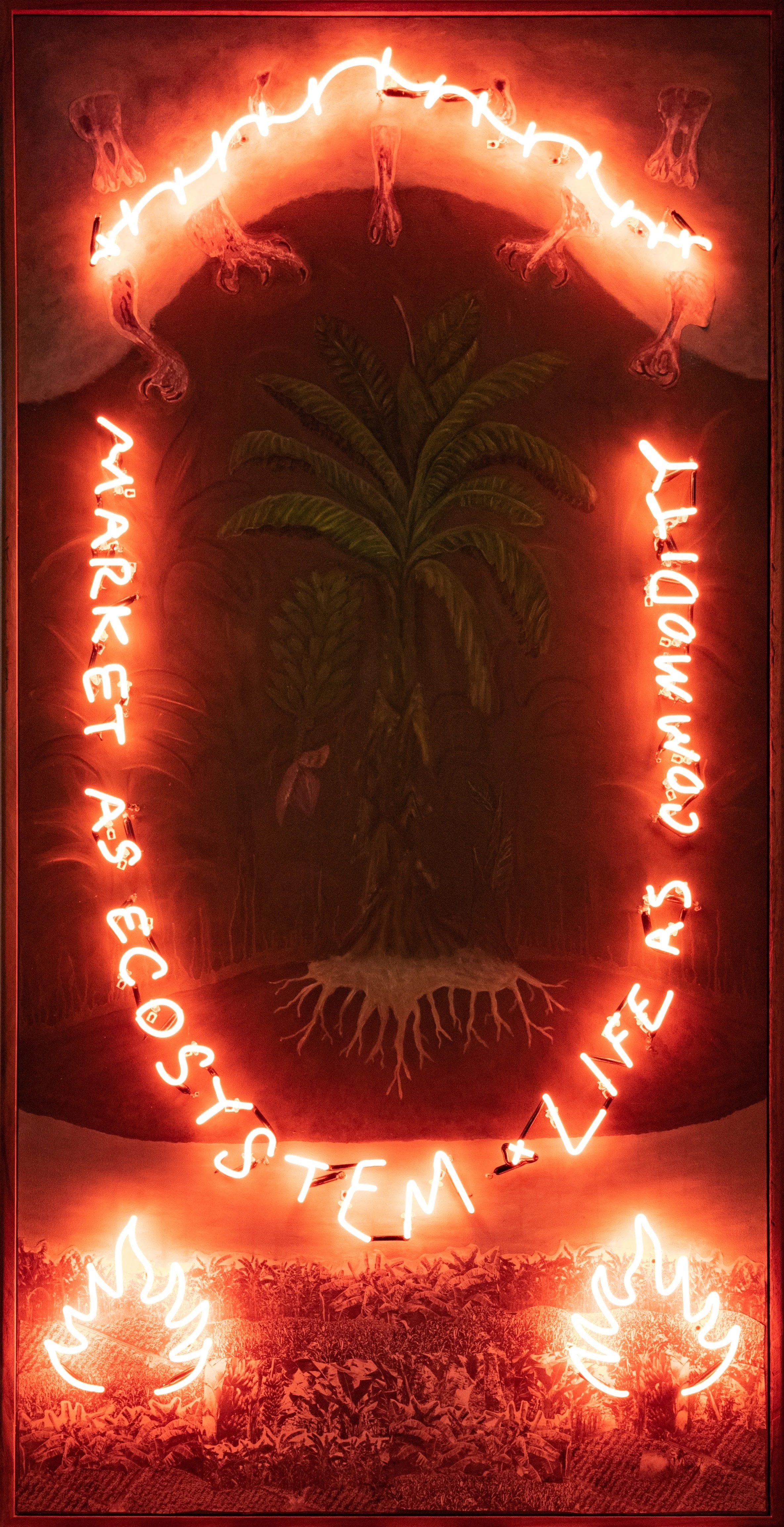

The Austere Enclave sets an inquiry on landscapes shaped by neoliberalism, connecting policy to geology and tracing the violent topographies and extractive tendencies of large dams and plantations -- two forms that demonstrate patterns in transforming nature into profit. The project interrogates politico-economic ideology, which actively terraforms land and renders them inalienable.

For this exhibition Dayrit speaks to Alyssa Paredes and Cla Ruzol.

CD: I’ve been looking into these two particular topics – large dams and cavendish banana plantations- as a way to understand and visualize neoliberalism. One way to do this is to try to think through these objects/spaces as landscapes. How do we view landscapes? As depictions of lived environments; as records of territory; as pictorial representation comprised of foreground, middle ground, background? In the context of landscapes, could you share some words to paint the scenery where banana plantations and dams are foregrounded within the background of neoliberalism?

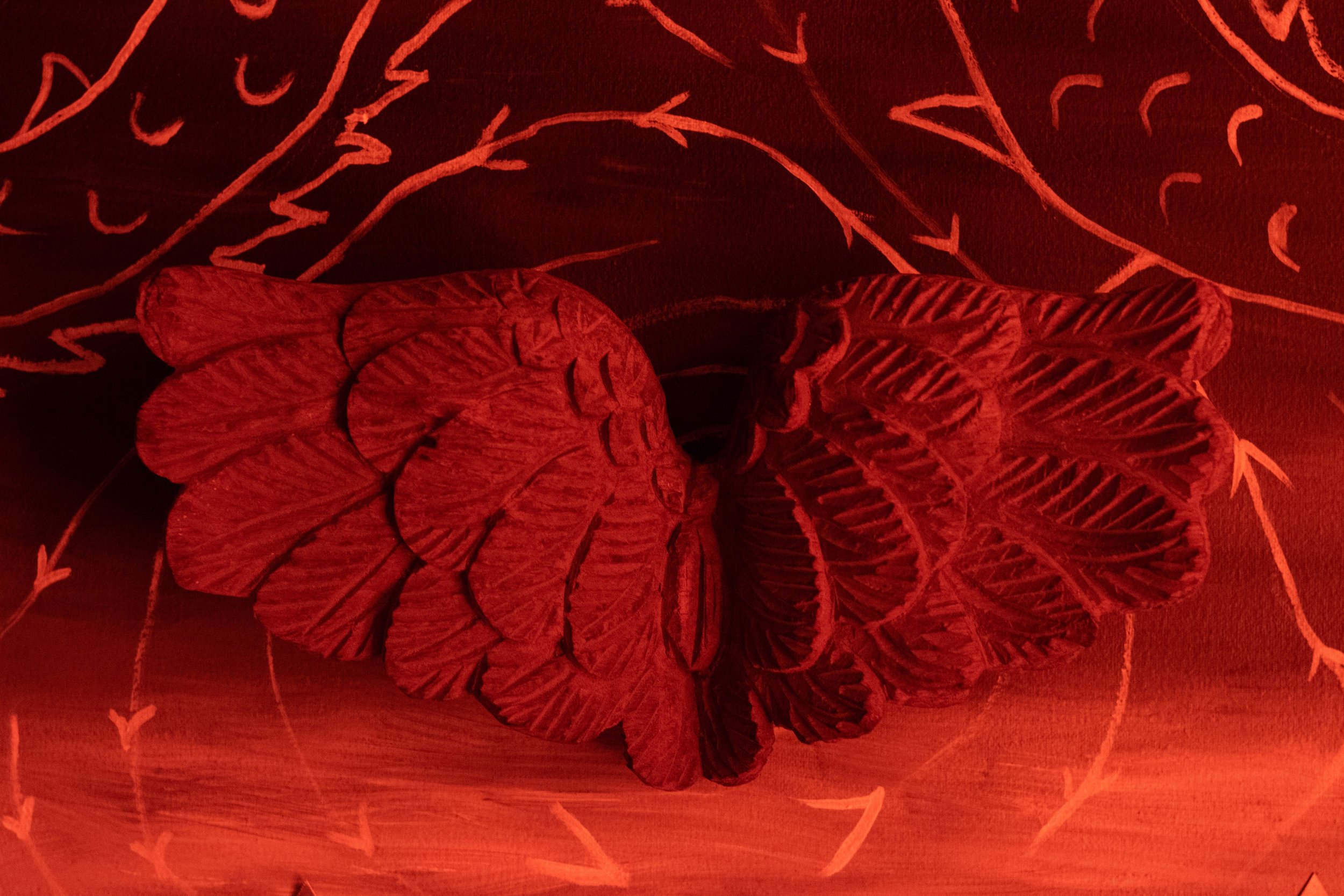

AP: When operating under plantation logics, everything about the natural world must be financialized. Living beings–birds, insects, plants, mollusks, and fungi–that naturally occupy green spaces but are not the cash crop in question, or do not contribute directly to its nutrition, are labeled as “weeds” and “pests.” Herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, and nematicides– all “life-killers” by etymological definition--eradicate these unwanted life forms, deemed valueless, in the name of “clean culture methods” and “modern scientific management.” The result is a neoliberal landscape that may have an impressively green canopy up above, but whose soil down below is a chalky light brown. On clean culture plantations, thick banana pseudostems stick out of the ground like lamp posts on a concrete street. Familiar life forms, like grasses, snails, worms, and bugs, are nowhere to be seen. Stray dogs and native chicken from nearby households stay away, likely attuned to the chemical haze that envelops the grounds. In the nighttime, the plantation is eerily silent, with not a single bird to be heard. The ironic thing is that several people will look upon this landscape and call it “beautiful.” Visitors to Mindanao, often coming from the Philippines’ urban centers, see the undisturbed canopy of green, and the unending, orderly rows of plants, and mistake it for “nature.” This modernist aesthetic, which sees beauty in a landscape of extreme and forced uniformity, are manifestations of neoliberalism’s inroads into the mind.

CR: When one pictures a dam, we imagine the monumental high wall made of concrete or earth that cuts across a river to hold water back. This infrastructure that artificially sticks out in the middle of a green forest cover is embedded in the web of state-market relations. Under neoliberalism, dams are a product of economic liberalization: the government reduces its spending by funding dams through a privatization scheme. It is deemed to be the “economical option” for governments where, like other resources that feed into the economy, “non-profitable” uses of water are removed, and the product is sold for profit by private corporations. When successfully built and water was conveyed, water extracted from the river would be monetized. What once was a river would now be labeled as “raw water”, “bulk water”, or “non-revenue water” depending on where it is on the value chain. The controlled flow of water passing through the dam ensures the uninterrupted flow of capital. A dam project is often designed as part of a system of dams. In this sense, the dam, and its accessory structures such as the reservoir, intake, outlet portal, tunnel, aqueducts, and treatment plants turn watersheds, mountain ranges, and the subterranean into a mega manufacturing infrastructure that stretches to over 50 km. If we follow the dams, we could map out in time and space both urban and industrial growth, as well as the encroachment of forestlands.

CD: Perhaps we can knit pick these landscapes based on their contrasts and contradictions. What are they and what are they not? What is their function and how can we interrogate these functions? We can start with their basic premise and dissect them in the following prompts.

“Walang yumayaman sa saging”

AP: In the language of the state, export Cavendish bananas are commonly referred to as “cash crops.” This means that it is grown primarily for its exchange value as an object of trade rather than for its use value as consumable food by the people who grow them. At first glance this makes intuitive sense for a Filipino population that prefers domestic varieties like latundan, lakatan, and saba over the tasteless Cavendish. Yet the very terminology of the “cash crop” begs scrutiny for the contradictions that it can obscure. An oft repeated phrase along Mindanao’s banana belt is “walang yumayaman sa saging” (No one gets rich on bananas). While the industry has promised job security for laborers, a receptive market for growers, and a steady flow of rent for small land lessors, intervening structures and tactics have left those promises unrequited. Graver still, many who engage in the business of bananas as contract growers describe themselves as milyonaryo sa utang (millionaires in debt). With costs of fertilizers, pesticides, and other inputs increasing exponentially, while buying prices of bananas remain the same sometimes for as long as thirty years, growers accrue balances to exporting companies with every monthly statement. A striking reality observable in Mindanao, then, is that communities who grow bananas are poorer now than they were to start.

CR: Damming rivers is a type of intensive resource extraction. Unlike other examples of large extractive industries, such as fossil fuel and mining, hydropower dams are presented as “clean, renewable sources” that provide electricity, irrigation, and domestic water. Dams are portrayed as the lesser but necessary evil that sustains economic progress. It can easily capitalize on the looming anxiety of a future without access to water particularly among city dwellers. Water privatization and the globalization of technology, including dam engineering, is well-funded and technically inaccessible to the public. This makes it easy for state authorities to conjure up a popular imagination that privatizing water is the only solution to a water crisis. But what they actually are, are speculations.

Metro Manila residents until today, as an example, are still afflicted with water interruptions after almost three decades of privatization. Damming new sources of water frames the water crisis as a problem of water supply to sustain the expansion of industries rather than to nourish communities. Dams do not address the true problem of inequitable distribution of water flow and pressure that connects elite urban spaces such as the port industry, large commercial districts, high-end condominiums, and gated subdivisions, while marginalizing settlement areas. The promise of clean water supply remains fictitious when the supposed clean tap water in Metro Manila remains to be doubted. People still buy filtered water retailed in blue jugs instead of drinking from the tap.

CD: The political and economic implications of these features are conceivably the most complicated to untangle. How would you map the historical and/or structural factors that enabled large dams and plantations to multiply/expand in the Philippines?

AP: The intertwined factors of colonial history, state bureaucracy, capitalist ideology, and interpersonal aspirations are responsible for the continued expansion of industrial plantations across the Southern Philippines. At the colonial and bureaucratic level, the interests of foreign and domestic elite interests in transforming the region into a site of extraction cannot be underemphasized. State-sponsored settlement brought Christian families, along with their work ethics, legal property systems, and political hierarchies, into the region to take up roles in both the plantocratic, managerial classes and the laboring rank-and-file, while Indigenous Lumad and Moro communities were dispossessed and pushed into the mountainous interior. Government concessions allowed companies to exceed constitutional limits in their acquisition of territories, and environmental regulations riddled with loopholes enable them to install themselves with little accountability. None of these historical developments would have been possible without the underlying ideologies that saw the island as a tabula rasa devoid of its own culture and history, and as a wasteland requiring the “civilizing” effects of settlement, but also as a rich, resource-filled region prime for conversion into the country’s “fruit basket.”

“The plantation industry was a dream and a promise that many small landowning settlers believed in.”

AP (cont.): But perhaps the most under appreciated factor behind plantation expansion is the role that non-corporate actors themselves play. The plantation industry was a dream and a promise that many small landowning settlers believed in. They signed onto contracts, entered into buyer-seller agreements, and sometimes even forfeit land painstakingly acquired through agrarian reform back to the economic elite. There are many instances where these processes happen through forced means like threats, intimidation, and bribes. There are other circumstances when they can appear voluntary, but are in fact the result of structural forces designed to squeeze the peasant class. Confronting the involvement of several actors beyond the plantocratic class is necessary for engaging the plantation industry politically.

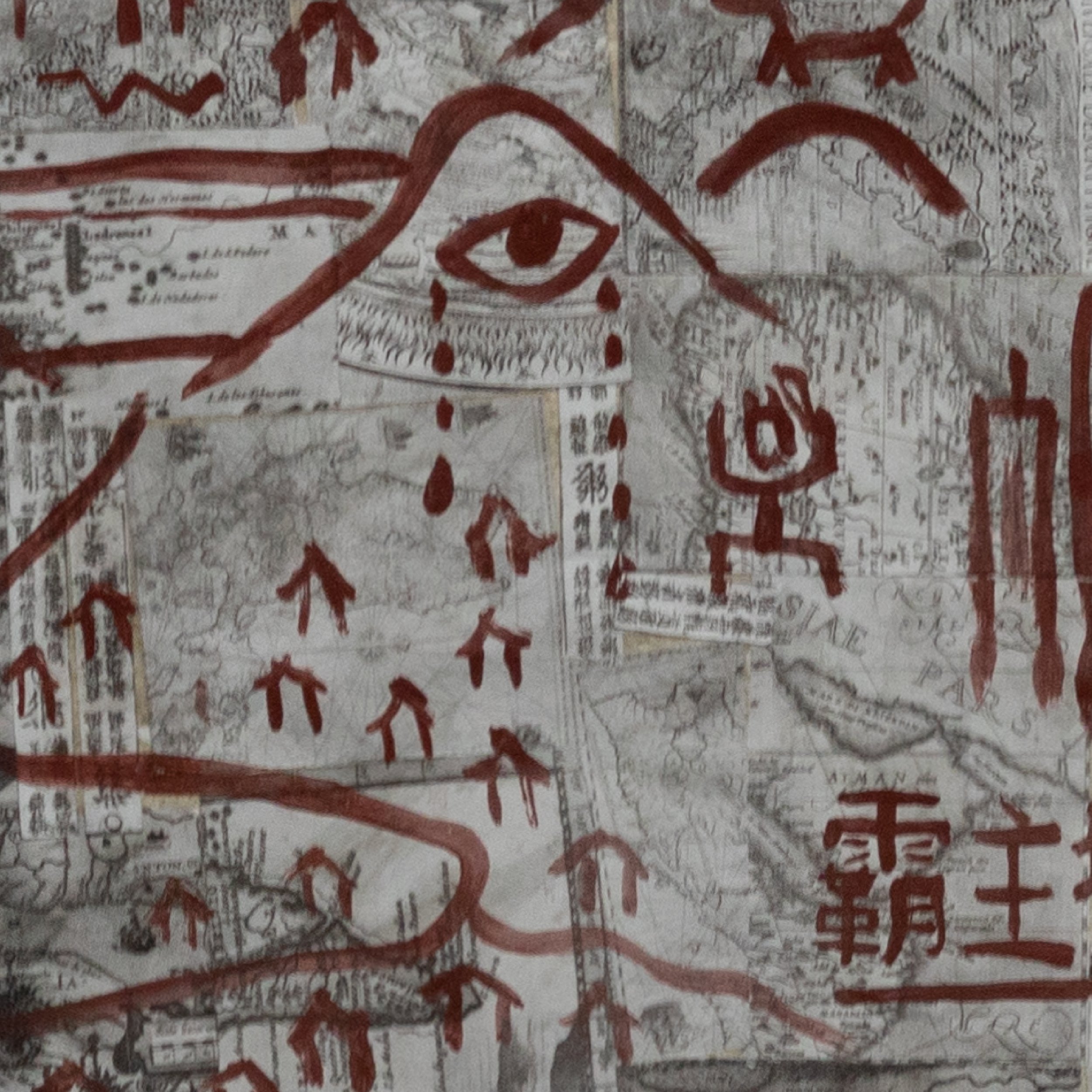

CR: Dam development in the Philippines is a planning strategy brought by the American military engineers during the colonial period and was carried on by US-trained Filipino engineers. Before the Second World War, the American engineer of the US Army and chief engineer of General Douglas MacArthur, Major General Hugh Casey, was tasked to survey the terrain of the Philippines for a system of hydropower development. This ground survey laid the foundations for the Maria Cristina Hydropower Plant on the Agusan River, the Caliraya Dam in Laguna, the Angat Dam in Bulacan, and many others. Harvesting hydropower was in fact the main purpose of a dam following the American model that Casey and the Filipino engineers after him were trained into. Compared to the electricity the dam would generate for economic development, irrigation and domestic water were considered secondary.

American military engineers were trained to build infrastructures from a standpoint of counterinsurgency which they put forward as “national security.” During the American imperialist invasion in 1898, Filipino revolutionaries held El Depósito, the underground reservoir in San Juan, as a stronghold. It was the waterworks that was the primary site of defense in Manila and consequently of conquest by the imperialist invaders who viewed the defending Filipinos as insurgents. The Montalban Dam was built strong enough to withstand explosives and was a site of guerrilla warfare during the Japanese occupation. The massive alteration of the terrain during dam construction favors the restriction of mobility, divides lands and communities, and fortifies encroached territories.

CD: Most prominent in the campaigns against large dams and plantations are the social and environmental effects. Could you outline these effects? How do human and nonhuman/ more-than-human intersections fare in these entanglements with capitalist logic?

AP: It seems an impossible task to summarize the environmental effects of an industry– the Philippine plantation economy–that has wholly reorganized the relationship between Filipinos and their natural environs. To begin, it is necessary to acknowledge that Land once dedicated to growing domestically consumable food items is now exclusively committed, by contractual law, to growing commodities to feed other nations instead. Where banana plantations have been established across Mindanao, there are several ways by which local communities become sinks for the byproducts of industrial agricultural activity. Nearby residents fall under fungicidal spraying at least two times a week. As a result of chemical drift, these communities speak about suffering chronic and undiagnosable illnesses, losing livestock and garden vegetables, and facing uncertainty about the potability of their water sources. Spatio-temporal lags between chemical exposure and the occurrence of symptoms make it extremely difficult to produce the kinds of evidence of harm that courts recognize as “scientific.”

Bananas rejected for cosmetic purposes are dumped on the sides of the road when private landfills are full, a regular occurrence. Streams and rivers carry chemical run-off, ecologically harmful synthetic fertilizers, and silt to surrounding natural bodies, processes compounded by frequent and heavy rainfall. In the dry months, by contrast, the demand for irrigating large expanses of land means plantation companies must buy water from local water districts, tap groundwater sources, or extract it from the underground water table. With its environmental externalities seeping out beyond its borders, and the ecological resources it absorbs into itself so vast, it seems pertinent to ask where the plantation begins and where it ends?

CR: Large dam projects have always been about what the state is willing to surrender for “national security and economic development” even when it meant irreversible changes to the communities and the ecology. When water is dammed, the relatively fast-moving rivers and streams that have been sustaining the downstream with nutrients, sediment, and organic life are replaced by a large reservoir of slowly moving or standing water. When the dam disrupts the natural flow of water, the landscape where villages, animals, and plant life that once thrived would be submerged underwater. The reservoir is a water bank as deep as how high the mountains once were. The sides of a mountain range used in farming, hunting, and gathering food and medicine, and as habitats of diverse wildlife species would become the reservoir’s canals and walls. It is alarming to learn that there is a boom in dam building in Southeast Asia amidst the lack of assessments of hydromorphological impacts of dams on rivers, which may lead to major damages in ecosystems downstream. The flow of nutrients from the river that enriches the downstream ecosystems including alluvial plains, estuaries, mangrove forests, seagrass beds, and coral reefs would be hampered. The function of dams as flood control had also fallen short. There were many records of flooding downstream due to the release of water from the reservoir. What the dam engineers could only do in these situations is to send an early warning to alert the people downstream of the incoming flood.

CD: Perhaps we can elaborate on the social costs of these features. Coming from social justice and human rights perspectives, how do large dams and plantations effect communities and the living conditions of Filipinos at large?

AP: Political silencing is the ultimate social cost of plantation hegemony in the Philippine South. While the industry’s threats to food security, human and environmental health, and Indigenous sovereignty are undeniable, the fact of the matter is that the plantation economy and other private institutions can often fill the social welfare gaps left by the absence of state provisioning. In various provinces of Mindanao, communities speak of improved infrastructure, market access, and employment since the arrival of industrial agriculture. Others attest that plantation companies have offered them medical and dental services, potable water sources, and social activities. Needless to say, the mere fact that plantations contribute to socioeconomic life says nothing about the quality of the laborer’s life, the distribution of incomes and dollars generated, and the environmental compromises such forms of extraction demand.

“Why bite the hand that feeds us?”

AP (cont.): But these relationships of patronage do have an affective force, at times imbibing local communities with a sense of loyalty, kinship, and adoration with and for the same institutions that bring them harm. Along a prominent plantation road in Davao del Norte, posters reading, “Why bite the hands that feed us?” are observable during moments of antagonism between company and worker. These sentiments can pit local communities against even the activists and advocates who aim to support them–like fighting cocks set against each other at the hands of their handlers. When such forms of self-driven political silencing occur, they can pose serious challenges to the pursuit of social justice and human rights.

CR: Dams are almost always located within ancestral domains of indigenous peoples. Similar to the effects of mining to indigenous communities, dams cause displacement, internal conflict among indigenous communities, unwilling reliance on wage labor, containment of mobility and access to forest and water resources, and assimilation to the market economy. Today and throughout the history of dams, the militarization of water sources has impacted communities through surveillance, intimidation, red-tagging, arrest, and extrajudicial killings. This is evident as early as the colonial era and which has recently intensified in the period of Duterte’s military authoritarianism (2016-2022) with the legislation of the Anti-Terror Law and the creation of the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTFELCAC). Privatization schemes also reproduce water scarcity by not addressing the infrastructurally unequal access and use of water across the urban and class divide. Instead, there is an apparent fixation with dam building. This is especially important when water consumers themselves are the ones paying the capital investments in the construction and the logistical bureaucracy that enables the processing of permits and consents. Such investments were initially funded by foreign loans, public-private partnerships, or private concessionaires but eventually would be paid by taxes and allocated in the water tariff.

CD: Would you consider the logic of justice more “natural”, so to speak? I am curious about how you see your scholarship bleed into social movements and other forms of resistance. If plantations and large dams present such dire contradictions, does the objective study of these objects/spaces inevitably expose unequal power relations and unjust structures? Do you feel that your work contributes to seeking justice?

AP: There is nothing inevitable that ties the quest for objective knowledge to the project of justice. For those who follow the discourse around the Philippine plantation economy, it is apparent that agribusinesses’ dire contradictions can often be glossed over by impressivesounding statistics, news features, and press releases. There is a way that members of industry can talk about the work they do in a self-congratulatory manner, positioning themselves as income-generators, infrastructure-builders, job-creators, and dollar-earners in the provinces that feel the most forgotten by the central government. As far as they are concerned, these too are “objective facts” that demonstrate how plantations contribute to the project of peace and development in the country. But those who experience and know the realities on the ground–in particular, the local communities and the activists, advocates, and scholars allied with them–see through those sleights-of-hand. They understand that agribusiness’ very ability to make such proud claims in the face of contradictory realities is itself a manifestation of unequal power relations and unjust structures that privilege certain forms of expertise over others. For these reasons, shining light through the cracks in the façade can be an act of justice. But this is not an inevitability, but rather the result of political intentionality. As an anthropologist studying the dynamics of the Philippines’ plantation economy, I hope my work contributes to seeking justice in two primary ways. First, I want my scholarship to help explain why, when, and how certain environmental movements succeed and why others fail. These were the questions at the forefront of my mind when thinking with Davao City’s Mamamayan Ayaw sa Aerial Spray (Citizens Against Aerial Spray) campaign, and its fate as it moved from Davao City Hall, to the Regional Trial Court, to the Supreme Court of the Philippines between 2005 and 2016, for example. Second, I want my research to illuminate the various ways that local communities expand political projects vis-a-vis the plantation. This is why I do immersive ethnographic fieldwork in Mindanao, as close to the ground as possible. As it is, political energy can be concentrated into agrarian reform campaigns and Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title advocacy. At their core, these are deeply important ways of disrupting the dominance of plantation regimes, but their revolutionary potential can also be compromised by private interests. My objective is to emphasize that these are also not the only forms of political mobilization that are available to people on the ground.

CR: Historically, the construction of legacy monuments had been pushed back despite its seemingly grand momentum. For example, in post-WWII, the increase in wages of the Metropolitan Water District (MWD) workers were considered a cause for construction delay and inefficiency. During the construction of the Bicti-Novaliches aqueduct in 1947, members of the Hukbalahap (Hukbong Bayan Laban sa Hapon) urged the MWD workers to demand higher wages and to call a strike if these demands were not met. The MWD management instead asked the Philippine Constabulary and the Armed Forces of the Philippines to install a detachment to patrol the area. When a strike was organized, empty workstations in the Balara filters were filled up by the Army Corps of Engineers. There were many more examples of resistance that were met with police power by the reactionary state. My work as an anthropologist explains with critical, historical, and empirical depth the lived water experiences in our society. Our tap water experiences would remain significantly unchanged until water infrastructures are being built massively to fill-in the equally massive demand for the growth of industries of the elite. Infrastructures for safe water should be reclaimed by the public as a common resource. My observations in my long-term ethnography among dam implementers also support the calls of social movements to defund the military and abolish the NTF-ELCAC. There is overwhelming evidence of how bureaucratic procedures in dam implementation were repurposed for policing both the movement of water and the deemed enemies of the state. The reallocation of funds from military exploits to the rehabilitation of the water system brings us closer to a just future of water.

Cla Ruzol is a PhD Anthropology candidate at the London School of Economics. Their research explores what it is like to be a government bureaucrat implementing a large dam project in the Philippines today. Cla is also a board member of the Ugnayang Pang-Agham Tao

(The Anthropological Association of the Philippines).

Alyssa Paredes is an environmental anthropologist doing research on industrial agriculture, transnational trade, and social movements. Originally from Manila, she has done fieldwork on the plantation economies of Mindanao, particularly Davao and Cotabato, since 2016. She is currently Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Cian Dayrit (b. 1989) challenges dominant perspectives of power and space through textile and other mediums. His works explore colonialism, archaeology, and history. Dayrit subverts the language and workings of institutions such as the state, museums, and the military to understand and visualize the contradictions on which these platforms or formats are built. He received the Ateneo Art Awards Fernando Zóbel Prizes for Visual Art in 2017 and is a Cultural Center of the Philippines Thirteen Artists Awards recipient. His works have been featured in biennials across the globe: Gwangju Biennale, Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, Dhaka Art Summit, New Museum Triennial “Songs for Sabotage” in New York, Göteborg Biennial, and at the 2022 Kathmandu Triennale. Dayrit has also participated in exhibitions at Para Site Hong Kong, Hammer Museum Los Angeles, the Metropolitan Museum of Manila, the Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw, Jameel Arts Centre, Dubai. His works were presented at Frieze London in 2019 and at Art Dubai in 2022. Dayrit completed artist residencies at Bellas Artes Projects in Bataan and at Gasworks, London.

Selected Works from The Austere Enclave