7 September - 5 October 2024

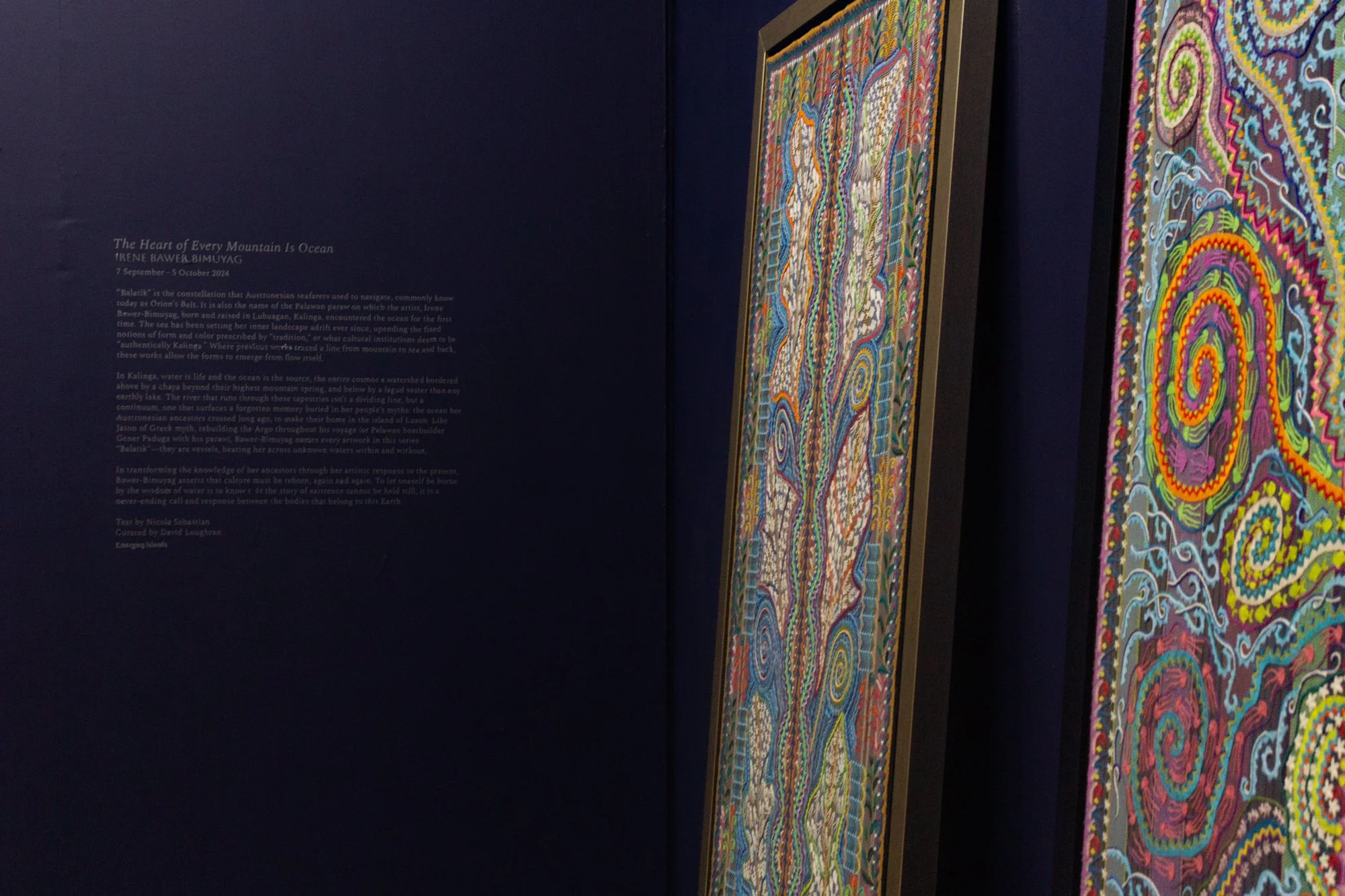

The Heart of Every Mountain Is Ocean

Irene Bawer - Bimuyag

Curated by Emerging Islands

The Heart of Every Mountain Is Ocean is the latest offering from textile artist Irene Bawer-Bimuyag’s long-term series, Balatik. The ancient name given by Austronesian seafarers to the constellation commonly known today as Orion’s Belt, Balatik is also the name of the boat in Palawan on which the artist, born and raised in Lubuagan, Kalinga, encountered the ocean for the first time. The ocean has been haunting her ever since, setting her inner landscape adrift, and upending the fixed notions of form, color, and pattern prescribed to her by “tradition,” or more accurately, by what cultural institutions have deemed to be “authentically Kalinga.”

Using the traditional Kalinga textile as a base, Bawer-Bimuyag has been slowly adapting the weaving techniques taught her by her mother and grandmother to capture her encounter with the sea: explosions of brilliantly coloured embroidery, instead of the conventional reds and blacks; the neat geometric symmetry meant to evoke the harmony of field and village, mountain and stars, upended by the pulsing currents and spiraling gyres of water that refuses to stand still; and the playful shapeshifting of forms that have been established for centuries, so that flowering plants morph into starfish, ferns into seagrass, and the pattern used to signify “house” is adapted to mean “coral.” “Now, it’s a home for the fish,” she says.

For the Kalinga, their sense of place is shaped by the flow of water, whose unceasing chatter can be heard from the forest and the field to the village, even inside people’s homes. In their collective imagination, the entire cosmos is a watershed, bordered above by a chaya beyond their highest mountain spring, and below by a lagud vaster than any earthly lake. Diving down into the Sulu Sea, looking up at the islands of Palawan as if they were mountains rising majestically out of the water, Bawer-Bimuyag felt “the connection between the mountain and the sea—how they cling to each other.” The artist had been raised to respect, conserve, and even fear the water—typhoons turn rivers violent, and she has lost family members to drowning incidents in the sea. But in Palawan she realized that “If water is life, then the ocean is the source.” It filled her with an urgent sense of responsibility. “I have to plant more, take care of my home more, because I know where all of it comes from.”

In following the water, and letting it reorder her world, she surfaces an ancient, forgotten memory buried deep in her people’s myths: the ocean that her Austronesian ancestors crossed long, long ago, to reach the island of Luzon and make their home in the Cordillera mountains. Yet, even beyond language, the mountains remember the ocean that holds them, still; every time the sun begins to rise, a sea of clouds flows through their valleys, and vanishes into thin air before noon. This, her father, the Kalinga teacher and culture bearer Sapi Bawer, says, is God.

Yet this exhibit charters new territory in the artist’s ongoing odyssey. Where previous works traced a line from mountain to sea and back, these new works allow the forms to emerge from flow itself. Working simultaneously across several textiles as if her very body were the shuttle of a loom, Bawer-Bimuyag draws inspiration from the visions that appear to her in the plants in her garden, the river stones lining her home. A traditional border runs down each tapestry, not a dividing line but a continuing one, a sign of respect to the river of space-time that brings balance, but also change.

All too often, contemporary Indigenous creativity is labeled as “craft” rather than “art:” fit for a trade fair, yet “out-of-place” in a contemporary art gallery. In transforming the knowledge of her ancestors through her artistic response to the present, Bawer-Bimuyag asserts that, for culture to be alive, it must be reborn, again and again. Much like Jason rebuilding the Argo over the course of his voyage (or Palawan boatbuilder Gener Paduga with his paraw), she names every artwork in this series Balatik—they are vessels bearing her across unknown waters within and without.

To let oneself be borne by the wisdom of water is to know that the story of existence cannot be held still; it is a never-ending call and response between the bodies—land and water, ocean and spring, plant and animal, highland and lowland—that belong to this Earth.

Text by Nicola Sebastian

Curated by David Loughran

Irene Bawer-Bimuyag (b. 1976) creates handwoven textiles that are a celebration of life. A designer, embroiderer, and weaver based in both Baguio City and Lubuagan, Kalinga, her geometric and organic patterns, use of color, and intricate embroidery respond to both traditional and contemporary making. She belongs to a long line of weavers in the Kalinga ancestral village of Mabilong, where backstrap looms are found in most homes, and where handwoven textile is sacred in ritual but has also evolved into a livelihood industry. Her work involves being part of an ecology of traditional motifs and symbols. But she also creates to expand this frame of reference.

In making new work, Irene Bawer-Bimuyag takes careful notes of where new patterns move a craft that speaks to where her community is at present, surrounded and often misunderstood by its placement in a formerly “outside world.” Her work, including in traditional dance, is empowered and informed by sustained movement, to take space and persist, to continue creating art that return them to collective ground origin, to the idea of making a home. Her work represents an examination of what material culture holds in both representation and the contemporary indigenous imagination.